Survivors

No doubt they'll soon get well; the shock and strain

have caused their stammering, disconnected talk.

Of course they're 'longing to go out again,'--

These boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk.

They'll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed

Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died, --

Their dreams that drip with murder; and they'll be proud

Of glorious war that shatter'd their pride...

Men who went out to battle, grim and glad;

Children with eyes that hate you, broken and mad.

-- Written by Siegfried Sassoon, 1917, while in a hospital for "war neurosis."

<<>><<>><<>><<>>

The term "thousand-yard stare" originated in WWII, but it's described in survivors of WWI. It's an expression that indicates dissociation from trauma, the mind's effort at protecting itself from too much horror.

When you hear the whistling in the distance your entire body preventively crunches together to prepare for the enormous explosions. Every new explosion is a new attack, a new fatigue, a new affliction. Even nerves of the hardest of steel, are not capable of dealing with this kind of pressure. The moment comes when the blood rushes to your head, the fever burns inside your body and the nerves, numbed with tiredness, are not capable of reacting to anything anymore. It is as if you are tied to a pole and threatened by a man with a hammer. First the hammer is swung backwards in order to hit hard, then it is swung forwards, only missing your scull by an inch, into the splintering pole. In the end you just surrender. Even the strength to guard yourself from splinters now fails you. There is even hardly enough strength left to pray to God.... A letter from a soldier at the front.

When you hear the whistling in the distance your entire body preventively crunches together to prepare for the enormous explosions. Every new explosion is a new attack, a new fatigue, a new affliction. Even nerves of the hardest of steel, are not capable of dealing with this kind of pressure. The moment comes when the blood rushes to your head, the fever burns inside your body and the nerves, numbed with tiredness, are not capable of reacting to anything anymore. It is as if you are tied to a pole and threatened by a man with a hammer. First the hammer is swung backwards in order to hit hard, then it is swung forwards, only missing your scull by an inch, into the splintering pole. In the end you just surrender. Even the strength to guard yourself from splinters now fails you. There is even hardly enough strength left to pray to God.... A letter from a soldier at the front.

From a diary written at the Battle of Verdun:

Alone, in a sort of dugout without walls, I pass twelve hours of agony, believing that it is the end. The soil is torn up, covered with fresh earth by enormous explosions.

In front of us are not less than 1,200 guns of 240, 305, 380, and 420 calibre, which spit ceaselessly and all together, in these days of preparation for attack. These explosions stupefy the brain; you feel as if your entrails were being torn out, your heart twisted and wrenched; the shock seems to dismember your whole body. And then the wounded, the corpses!

In front of us are not less than 1,200 guns of 240, 305, 380, and 420 calibre, which spit ceaselessly and all together, in these days of preparation for attack. These explosions stupefy the brain; you feel as if your entrails were being torn out, your heart twisted and wrenched; the shock seems to dismember your whole body. And then the wounded, the corpses!

Never had I seen such horror, such hell. I felt that I would give everything if only this would stop long enough to clear my brain. Twelve hours alone, motionless, exposed, and no chance to risk a leap to another place, so closely did the fragments of shell and rock fall in hail all day long.

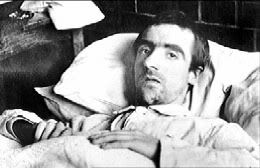

They called it "war neurosis," "soldier's heart" or "shell shock." Col. Frederick Hanson described its effects in 1943:

They walked dispiritedly from the ambulance to the receiving tent, with drooping shoulders and bowed heads. Once in the tent they sat on the benches or the ground silent and almost motionless. Their faces were expressionless, their eyes blank and unseeing, and they tended to go to sleep wherever they were. The sick, injured, lightly wounded, and psychiatric cases were usually indistinguishable on the basis of their appearance. -- PTSD Compensation and Military Service

Post-traumatic stress disorder wasn’t understood at the time. Doctors thought the soldiers who exhibited mental disturbance must have been physically injured in some way, their brains jarred around in their skulls by having a shell explode too close, perhaps. Men who broke down under the strain were derided as being “cowards,” which is one reason ilitaries didn’t want to recognize PTSD as real; they thought it would encourage “cowards” to use it as an excuse to get out of fighting.

Post-traumatic stress disorder wasn’t understood at the time. Doctors thought the soldiers who exhibited mental disturbance must have been physically injured in some way, their brains jarred around in their skulls by having a shell explode too close, perhaps. Men who broke down under the strain were derided as being “cowards,” which is one reason ilitaries didn’t want to recognize PTSD as real; they thought it would encourage “cowards” to use it as an excuse to get out of fighting.

Soldiers were sometimes executed during WWI for breaking down under the strain and fleeing.

Private Thomas Highgate was the first to suffer such military justice. Unable to bear the carnage of 7,800 British troops at the Battle of Mons, he had fled and hidden in a barn. He was undefended at his trial because all his comrades from the Royal West Kents had been killed, injured or captured. Just 35 days into the war, Private Highgate was executed at the age of 17.

Many similar stories followed, among them that of 16-year-old Herbert Burden, who had lied that he was two years older so he could join the Northumberland Fusiliers. Ten months later, he was court-martialled for fleeing after seeing his friends massacred at the battlefield of Bellwarde Ridge. He faced the firing squad still officially too young to be in his regiment.

To their far-off generals, the soldiers' executions served a dual purpose - to punish the deserters and to dispel similar ideas in their comrades. Courts martial were anxious to make an example and those on trial could expect little support from medical officers. One such doctor later recalled, 'I went to the trial determined to give him no help, for I detest his type - I really hoped he would be shot.' -- BBC (Note: The men in the above article have since been pardoned posthumously.)

Dr. Frederick Walker Mott wrote a description of a soldier under his care

He belonged to a Highland regiment. He had only been in France a short time and was one of a company who were sent to repair the barbed wire entanglements in front of their trench when a great shell burst amidst them. He was hurled into the air and fell into a hole, out of which he scrambled to find his comrades lying dead and wounded around. He knew no more, and for a fortnight lay in a hospital in Boulogne. When admitted under my care he displayed a picture of abject terror, muttering continually, "no send back," "dead all round," moving his arms as if pointing to the terrible scene he had witnessed.

There aren’t many statistics for European soldiers in this regard. Unfortunately, a large portion of the WWI records were destroyed in the bombings of WWII. We do know from pension records that by 1929, the British military was paying a pension to about seventy-five thousand “neurological cases,” men completely disabled by their wartime traumas. The real number of PTSD sufferers was probably far higher.

There aren’t many statistics for European soldiers in this regard. Unfortunately, a large portion of the WWI records were destroyed in the bombings of WWII. We do know from pension records that by 1929, the British military was paying a pension to about seventy-five thousand “neurological cases,” men completely disabled by their wartime traumas. The real number of PTSD sufferers was probably far higher.

"Anyone who has not seen these fields of carnage will never be able to imagine it. When one arrives here the shells are raining down everywhere with each step one takes but in spite of this it is necessary for everyone to go forward. One has to go out of one's way not to pass over a corpse lying at the bottom of the communication trench.

Farther on, there are many wounded to tend, others who are carried back on stretchers to the rear. Some are screaming, others are pleading. One sees some who don't have legs, others without any heads, who have been left for several weeks on the ground..." Letter from a soldier at the front, Verdun, 1916.

The United States sent nearly two million soldiers to Europe. 159,000 of them were taken from the lines for psychological reasons. About half were permanently discharged for it.

Hemingway himself may have suffered from it. Some of his characters certainly did. It appears in other early 20th century works, a reflection of the society authors saw around them, and the struggle to understand what had happened to these men.

Hemingway himself may have suffered from it. Some of his characters certainly did. It appears in other early 20th century works, a reflection of the society authors saw around them, and the struggle to understand what had happened to these men.

In

Mrs. Dalloway,

Virginia Woolf writes about the incompetent treatment given to soldiers asking for help:

There was nothing whatever the matter, said Dr. Holmes…When he felt like that he went to the Music Hall. He took a day off with his wife and played golf. Why not try two tabloids of bromide dissolved in a glass of water at bedtime?

Soldiers in the modern era still struggle with PTSD. Studies suggest that around 10% of soldiers will be afflicted by it. (Up to 30% of Vietnam veterans were affected.) Though we know more about PTSD now and have better methods of treatment, soldiers sometimes don't want to admit they're struggling. There are many resources available to assist soldiers and their families. If you or someone you love are struggling with it, please reach out. No one should have to fight this battle alone.

When you hear the whistling in the distance your entire body preventively crunches together to prepare for the enormous explosions. Every new explosion is a new attack, a new fatigue, a new affliction. Even nerves of the hardest of steel, are not capable of dealing with this kind of pressure. The moment comes when the blood rushes to your head, the fever burns inside your body and the nerves, numbed with tiredness, are not capable of reacting to anything anymore. It is as if you are tied to a pole and threatened by a man with a hammer. First the hammer is swung backwards in order to hit hard, then it is swung forwards, only missing your scull by an inch, into the splintering pole. In the end you just surrender. Even the strength to guard yourself from splinters now fails you. There is even hardly enough strength left to pray to God.... A letter from a soldier at the front.

In front of us are not less than 1,200 guns of 240, 305, 380, and 420 calibre, which spit ceaselessly and all together, in these days of preparation for attack. These explosions stupefy the brain; you feel as if your entrails were being torn out, your heart twisted and wrenched; the shock seems to dismember your whole body. And then the wounded, the corpses!

Post-traumatic stress disorder wasn’t understood at the time. Doctors thought the soldiers who exhibited mental disturbance must have been physically injured in some way, their brains jarred around in their skulls by having a shell explode too close, perhaps. Men who broke down under the strain were derided as being “cowards,” which is one reason ilitaries didn’t want to recognize PTSD as real; they thought it would encourage “cowards” to use it as an excuse to get out of fighting.

There aren’t many statistics for European soldiers in this regard. Unfortunately, a large portion of the WWI records were destroyed in the bombings of WWII. We do know from pension records that by 1929, the British military was paying a pension to about seventy-five thousand “neurological cases,” men completely disabled by their wartime traumas. The real number of PTSD sufferers was probably far higher.

Hemingway himself may have suffered from it. Some of his characters certainly did. It appears in other early 20th century works, a reflection of the society authors saw around them, and the struggle to understand what had happened to these men.

War is a nightmare

ReplyDelete